What the GOP can learn from its third-party past

The 1912 Progressive Party Convention (From Library of Congress)

The idea of a third-party alternative for #NeverTrump Republicans seems to be over.

A key filing deadline for independent candidates in Texas has passed, Mitt Romney has stopped recruiting candidates, and after much distress, Republicans have begun to fall in line behind their presumptive nominee.

As unpredictable as this election has been so far, a third-party run still appears implausible. That tells us something about how American politics organizes around parties, policies, and people.

Especially since the Republican party began as a third-party, the party’s past might inform how it handles its current identity-crisis.

Forgetting how we used to vote

The filing deadlines, ballot signatures, and quirks of primaries and caucuses that prevent third-party candidacies–all features of the modern campaign–make it seem as though the two-party system is somehow enshrined into law.

Lisa Disch, a professor of political science at University of Michigan, said the country wasn’t always like that.

“Today people might mistake our two parties as something constitutionally mandated,” Disch said.

How the country used to vote, by literally placing ballots into a box, demonstrates a forgotten past of our political choice. Parties used to print their own tickets to deposit into ballot boxes instead of picking candidates from state issued ballot in a voting booth.

In the modern era, the two major parties have consolidated the choices on that ballot. So while third-parties might serve as “harbingers for the future” ideas of the major parties but they rarely develop into governing or effective opposition.

“Ross Perot or Ralph Nader still can get on the ballot,” Disch said. “But they run for ideological purposes rather than creating any organization.”

America was never founded on parties

Historian Sean Wilentz argues in his book The Politicians and The Egalitarians, that an “anti-partisan” impulse has been part of the American attitude since the republic was conceived.

Historian Sean Wilentz argues in his book The Politicians and The Egalitarians, that an “anti-partisan” impulse has been part of the American attitude since the republic was conceived.

In fact, the Founding Fathers designed the United States constitutional system almost deliberately designed against parties. The Founding Fathers distrusted parties and factions. George Washington famously warned against their influence in his Farewell Address.

The premise of the American Revolution lays bare a contradiction about self-government: in the absence of a king, how can you organize around ideas without forming parties, how do you lead without becoming tyrants?

Even Thomas Jefferson, a vocal critic of parties and factions, formed the Democratic-Republican party to oppose John Adams’ Federalist party, losing to Adams in 1786 and defeating him in 1800.

Wilentz outlines how the tension between political parties and popular frustrations runs through the country’s history.

In fact, the origins of the Republican Party emerge from those tensions when Martin Van Buren’s creates a single-issue third party as an alternative to the populist Democratic party and the incremental Whig party.

A Currier & Ives cartoon about Martin Van Buren titled “The Modern Colossus” depicts the former President jumping from the Democratic party to the Whigs and Abolitionists. (From Library of Congress)

“It’s highly ironic that Martin Van Buren, who’s often thought of as inventor of the political party or at least a technician of the Jeffersonian-Jacksonian Democratic party, runs as a anti-slavery Free Soil candidate,” Willentz said. “That tells you a lot about the issues at stake.”

Van Buren left the presidency in 1841 as a Democrat and ran again in 1848 as a Free Soil candidate in 1848. His departure from the party he built demonstrates a clear decision on the divisions of his day.

“The point here is political parties have internal histories,” Willentz said. “There’s nothing static about it, he didn’t reject the idea of the party but what the party had come to be.”

Finding a platform to stand on

While pundits talk about a Republican civil war today, we forget that the party itself emerged from drastic divisions in the country.

“Sectionalism over slavery broke both the Whigs and the Democrats apart,” Wilentz said. “By the 1850s, the Democratic party lost its anti-slavery wing and became the party of the slave south, the Whigs lost the north, nativists began building their own parties.”

“Dividing the National map,” an 1860 satirical cartoon about the sectionalism before the Civil War. (From Library of Congress)

This disarray among the Whigs and the Free Soil party produced the conditions for the Republican Party and Lincoln’s unlikely election. Lincoln’s reputation and the future of the Republican party would not even find firm ground until after his assassination.

“One of the things about most modern third parties is they never last because they often aren’t designed to last,” Wilentz said. “They can have an impact on an issue as powerful as slavery, but they haven’t gone on because of the way American politics has been structured, first across the finish line wins, almost impossible to become a viable party.”

Popularity with the people

Fast forward to the early 20th century and the Republican party has endured through the corruption scandals of Grant’s presidency, retooled to the reforms of the Gilded Age but faces popular support for direct democracy through direct election of senators and primary contests, threatening the old guard of the party’s incremental.

Perhaps the most famous third party challenge started from inside the Republican party with former president Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt finished his presidency in 1908 and chose William Howard Taft as his successor to the Republican party.

The two men fell out when party divisions between Roosevelt’s progressive wing and Taft’s conservative wing came to blows over a litany of policy issues.

“SALVATION IS FREE BUT IT DOESN’T APPEAL TO HIM”- A 1912 cartoon from the magazine Puck, in which Teddy Roosevelt attempts to baptize the Republican party and President Taft in the salvation of ‘Teddyism.’ The Third-Party Choir sings: “And sinners bathed beneath that flood lose all their guilty stains. (From Library of Congress)

“Roosevelt actually wins the primaries but loses the nomination at the convention because the party decides to stick by a sitting president,” Wilentz said. “It wasn’t until 1968 that primaries became as central as they are now.”

Roosevelt was furious, and he left the Republican convention to form his new party.

“Roosevelt thought he had the backing of the people,” Wilentz said. “He was no shrinking flower.”

In his book, Wilentz describes the Progressive Party, often referred to as the Bull-Moose party, as “the political party to end all political parties.”

“A lot of it was anger and bitterness was similar to the bitterness that helped propel Van Buren to run,” Wilentz said. “The parties were dividing, there was almost fratricide within the parties… Roosevelt thought Taft had sold out his Square Deal.”

Though Roosevelt outpaced Taft in the general election, their split (along with the Socialist candidate Eugene Debs garnering 6 percent of the popular voted) handed the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, who would adopt some of the progressive reforms.

“Third parties are sometimes a sign of something in a party that is dying off,” Wilentz said.

What doesn’t kill the party makes it stronger?

Julian Zelizer, a professor of history at Princeton, said that parties either deflect from or draw in discontented voters because that’s what they’re designed to do.

1968 editorial cartoon by Herbert Block showing Presidential candidate George Wallace tailoring a coat, “3rd Party” and “Law and order talk”, to fit over the robe, “Racism”, of a Ku Klux Klan member and Wallace supporter, holding sign, “Wallace for President.” (From Library of Congress)

“Political parties are strong, muscle in organization, muscle in money, muscle in how people identify,” Zelizer said. “Even if you don’t like politics, the winner-take-all lends does not lend itself to third parties.”

The power of party organization means that third party constituencies more often get brought into the larger party, and sometimes fail to spoil the dominant party’s bid.

For example, George Wallace’s presidential run in the Democratic primary in 1964 and his segregationist American Independent run in 1968 outlined Nixon’s famous Southern Strategy.

“Wallace was pretty powerful,” Zelizer said. “He played effectively to disaffected Democrats. He was wrong on social policy, and his tone on race relations had a similar sentiment to Donald Trump.”

While Trump’s rhetoric echoes Wallace, there’s one major difference for the choice the Republican Party now faces: Trump’s inside the party, not out.

How Did George Martin Earn The Title of ‘Fifth Beatle’?

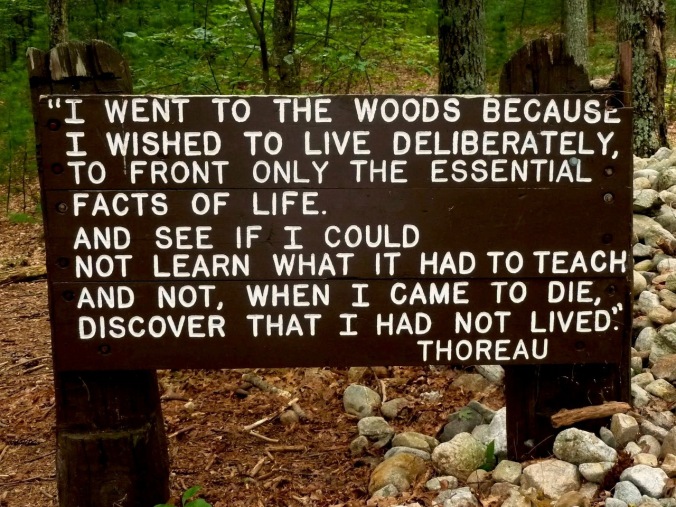

Speech: Bringing Public Media Out of the Woods

I wrote this speech for my speechwriting class at American University. It ties some of Henry David Thoreau’s complaints and lessons about the media of his day to the need for open-minded public media today.

A recent Washington Post article wrote that NPR listeners are graying. So in an effort to stay hip with the Millennial crowd, I’m going start with a story about someone who was streaming before it was cool, the 19th century Transcendentalist, Henry David Thoreau.

Before the American Civil War, Henry David Thoreau pled for the country to consider the character of John Brown, a man who attempted an insurrection against slavery and predicted a war over it.

Thoreau asked how herds of newspapers and magazines felt “obliged to get their sentences ready for the morning edition” while they refrained from publishing Brown’s exact words for fear of losing subscribers. Thoreau asked,

How then can they print truth? If we do not say pleasant things, they argue, nobody will attend to us. And so they do like some traveling auctioneers, who sing an obscene song in order to draw a crowd around them.

Thoreau’s call for calm and character fell on deaf ears amidst the clamoring office-seekers and speechmakers who made a cackling for conflict. With a Civil War, he witnessed the consequence of a press too cowered to question the conventional wisdom.

Thoreau’s quiet ideas echo loudly in our era of instant digital reaction, the 24-hour news cycle, and the public’s chronic distrust of journalism. Thoreau’s wisdom should be public media’s mission.

When public problems present themselves, the public needs a press it can trust.

Just as the printing press expanded the reach of the written word, television, radio and the Internet give people more options than ever. But this widened horizon of choice presents a paradox.

As more news must now compete for our attention, we have less time to make media choices critically. Commercial concerns create echo chambers and competition amplifies conflict. As entertainment and information compete for attention, we risk mixing news with the trivial.

In “Life Without Principle,” Thoreau laments the superficial discussions about news and politics but says we should not ignore them.

He argues newspapers and conversation ought to observe a “chastity of mind,” treating our thinking as a public space to be kept clear of dust, bustle, and filth.[1]

A free press is like a river. It should be broad, not shallow. The free flow of information should enable listeners to learn and grow and challenge thinking. That’s how we build a foundation of trust in society.

The Concord River, which leads into Walden Pond. (Photo by Frank Murmann)

Today, polls show record levels of public distrust for both the press and the government. Our dissatisfaction might stem from increased partisanship, a sense that networks value celebrity over substance, or a feeling of powerlessness on the behalf of citizens.

National Public Radio’s original mission statement in 1970 suggests an alternative. It built a news organization that begins “with no identity of its own” and refused to “substitute superficial blandness for genuine diversity.”

A media that serves the individual and promotes personal growth will build trust by “encouraging a sense of active, constructive participation, rather than apathetic helplessness.”[2]

News is only helpful if the audience feels it has relevance to their lives and they can take action. Those civic efforts only feel relevant if we build trust.

Information is essential but the expense in gathering it challenges journalism fundamental freedom from influence.

Conventional news is disappearing. With $46 billion dollars in ad revenune, Google now makes more on ads than what the entire newspaper made in 2001. Today those papers make about half as much.[3] Google’s motto may have once been “don’t be evil,” it is not bound to any sort of journalistic integrity. Google’s success does point to what people truly value: information.

Algorithms may make a more complex world easier to manage, but that news can’t exist without reporters on the ground. Popularity as measured by views or clicks won’t always support the journalism that needs to hold power accountable.

Today, more than ever we need media devoted to the public good. Free from partisan loyalties, conflicts of interest, or government control. Public media’s model isn’t perfect but its discipline provides the best path forward to truth.

With that in mind, we have to remember that reporting comes first.

Fred Rogers once said, “The greatest gift you ever give is your honest self.” That honesty comes from being an honest listener as well as an honest speaker. More often than not, this means newsgatherers ought to give priority to their subjects in stories. We need to tell stories with the people rather than telling them how to think.

Giving people their chance to be heard. That’s how a story can transport listeners to other people’s lives, other people’s countries, other people’s understanding. When you treat your audience with respect, there’s no need to interpret stories for them. They speak for themselves. Truth becomes self-evident.

Sometimes the most simple story speaks volumes. On 9/11, Robert Siegel happened to be in Manhattan. While televisions turned on the instant ticker, Siegel described the scene—the smoke in the air, the volunteers on the ground.

He found papers from the World Trade Center—a resume for a restaurant, some court hearing documents—and he used them to contact people who were there.[4] Instead of pontificating about how this moment changed everything, he told those people’s stories.

When Thoreau wrote, “speech is for the convenience of those who are hard of hearing; but there are many fine things which we cannot say if we have to shout,” he was referring to why we shouldn’t yell in the woods.

If we consider Thoreau’s message of self-discovery, personal growth, and peace of mind, we can forge public media’s path. If we listen, maybe we’ll find the wisdom to face the challenges of our day.

[1] http://thoreau.eserver.org/life2.html

[2] http://transom.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/NPRMISSION.pdf

[3] https://gigaom.com/2013/04/11/two-charts-that-tell-you-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-future-of-newspapers/

The smoke-filled room is dead! Long live the smoke-filled room!

Before Paul Ryan settles into the Speaker’s chambers, there’s one last order of business to “clean out the barn” as John Boehner departs: get rid of the cigarette smell.

As the final frontier for the dead-metaphor of the “smoke-filled backroom,” Boehner’s office was one of the last places untouched by D.C.’s citywide ban on smoking in 2007. Ryan compared the smell to a hotel room or rental car that has been smoked in.

Smoking as a metaphor of gritty work and dirty compromises

Smoking has long served as a symbol of “getting things done” in American politics, for better or worse. Before Washington was ever built, the Founding Fathers smoke and drank their way through the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

Before the revolution even, John Adams described a Boston Caucus meeting in 1763 that would gather “selectmen, assessors, collectors, fire-wards, and representatives are regularly chosen in the town… there they smoke tobacco till you cannot see from one end of the garret to the other.”

Nearly a hundred years later, Speaker James G. Blaine, the last Speaker to be elected to the Presidency, would initiate the first ban on smoking while in session in the galleries and the House floor in 1871.

By 1896, the House would prohibit smoking at all times in the House Chamber. As future Speaker of the House David Henderson of Iowa said proposing the rule, “members have been killed not alone because of the polluting effects of tobacco, but generally because of the impure air in this Hall.”

A press cliché rises from the ashes

Relegated to the cloakrooms, tobacco became jargon for a more clandestine type of politics. William Safire’s The New Language of Politics (1968) describes a “smoke-filled room” as a “place of political intrigue and chicanery.”

The Blackstone Hotel in Chicago, where a “smoke-filled room” of party bosses chose Warren G. Harding for their presidential candidate.

Safire recounts an infamous story where Republican Party leaders selected Warren G. Harding as a compromise candidate for president in the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago after a deadlocked convention in June 1920.

Associated Press reporter Kirke Simpson wrote at the time, “Harding of Ohio was chosen by a group of men in a smoke-filled room early today” and a political cliché was born.

Smoking sometimes became a shorthand for the “bossism” exemplified by Tammany Hall politicians, but individually elected officials didn’t face a stigma for smoking.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson – all smokers elected to the Presidency before the surgeon general warned of nicotine’s harms in the mid-1960s. As Sarah Kliff wrote for Vox, laws began to limit smoking in public and indoors. Smoking in the American public decreased from 45 percent in 1955 to 25 percent by the 1995.

Over that time, cigar smoking remained common in committee meetings. As Orrin Hatch remembered in Newsweek about working with Ted Kennedy, “the degree to which we were fighting was evident by the cloud of smoke Ted would send my way.”

The end of smoking in Washington fights?

As the nineties came along, the Clinton administration issued executive orders limiting smoking in federal buildings and pushed for banning smoking in public buildings. D.C. banned smoking in public buildings when it went smoke-free in January 2007.

Anticipating the ban and Nancy Pelosi’s rise to Speaker, there were whispers in late 2006 about banning tobacco from the Speaker’s Lobby, as this whimsically pun-filled report from The Washington Post identifies the culprit from Ohio as a main offender against Henry Waxman’s lungs:

As many as 25 percent of House members smoke, and one of the heaviest smokers is Majority Leader John A. Boehner (R-Ohio), who frequently emerges from the House floor and heads straight to the Speaker’s Lobby to consume his favorite brand, Barclay. Yesterday, when he stepped out of the chamber, he gestured to an approaching reporter that he needed a moment before talking. He made a beeline for the southwest corner of the room, pulled a cigarette from his breast pocket, lit it and inhaled deeply.

Banning smoking the speaker’s lobby was one of Pelosi’s first acts as speaker in 2007. After the Republicans took back the House in the 2010 elections and forced John Boehner and Barack Obama to negotiate through tense debt limit showdowns in 2011, Bob Woodward glimpsed what negotiations look like in a transition to a smokeless Washington:

They’re having these private meetings in the White House—what Boehner calls the merlot and Nicorette meeting…on the patio off the Oval Office… Boehner’s having merlot and smoking a cigarette, and the President is having ice tea and chewing a Nicorette to keep him from going back to smoking.

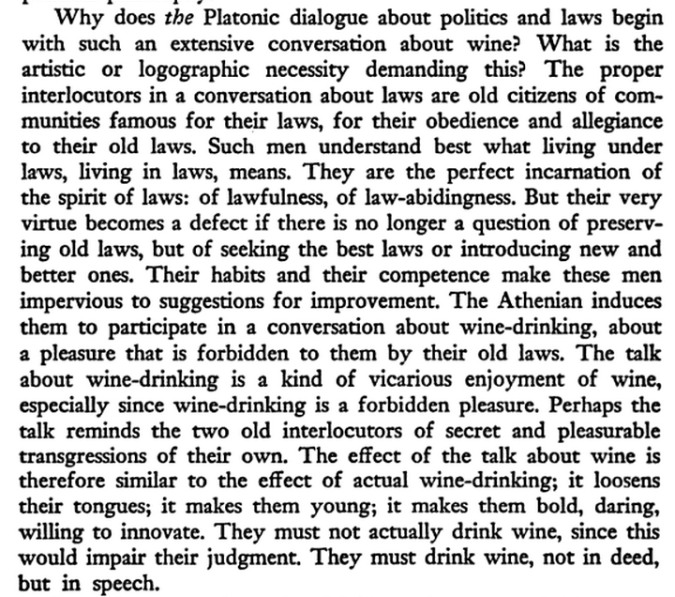

What Does Wine Have to Do with Politics?

Hilarious Clinton: On Comedy and Politics

Like most newshounds, I consume political humor like middle schoolers snack on Doritos. It’s not always good for us, but we’ll still chomp down the whole bag.

Philosophers like Plato and Aristotle warned against the danger that sophistry— a subtle, tricky, superficially plausible, but generally fallacious method of reasoning — posed to a democracy.

Plato argued through a depiction of Socrates that a governing republic ought to ban poets because their poems misrepresent what they imitate with words and “maim the thought of those who hear them.” Socrates’ depiction in Aristophanes’ comedic play, The Clouds, arguably led Socrates accusers to convict and execute him for corrupting the young.

The Clouds portray Socrates as a man who foolishly investigates the heavens and the earth and whether the buzzing sound gnats make are farts. He’s ridiculed for thinking that the clouds, not Zeus, make rain.

Aristotle identified comedy as poetry which imitates less than virtuous characters, often making people seem worse than they are by portraying the “ridiculous, which is a species of the ugly.” He valued wit as “educated insolence,” but condemned comedic poets for “when they use tunes that violently arouse the soul” to produce catharsis, or emotional release. Laughter, as Aristotle argues, is a manifestation of scorn.

But Comedy clearly provides a kind of medicine for the mind and soul. It resolves contradictions, highlights ignorance, and relieves intellectual stress. Comedy sometimes has no more failures in Knowledge than the nonsense of political speeches. Inevitably, the American people want to be moved, not lectured.

In 2008, Clinton mocked Barack Obama for his poetic language, pointing the ridiculous:

“The skies will open, the light will come down, celestial choirs will be singing and everyone will know we should do the right thing and the world will be perfect.”

But as with all good humor, Hillary might be surprised. To strike a balance between the inspiring and the informative to attain the coveted gilded truth of authenticity, she might need imitate what she mocked about Barack or else become the joke herself.

Rain or Shine: Umbrella Fact-Drop

Photo of Representative William D. Upshaw of Georgia, a leader of the drys, standing on railing with crutch and holding umbrella, with dome of the U.S. Capitol under the umbrella, April 20 1926.

A few facts to drop or paraphrase about umbrellas for today’s rainy day:

- The oldest written reference to an umbrella is 21 AD for Wang Mang’s ceremonial four-wheeled carriage. The Chinese character for umbrella 傘 is a pictogram.

- A sanskrit epic, Mahabharata relates the legend of a bow shooter, Jamdagni, who had his wife, Renuka, recover his arrows. When she returned late from fetching arrows, she blamed the heat of the son, and he shot an arrow at the sun. The sun begged for mercy and offered Renuka an umbrella.

- Parasols, or umbrellas for the sun, were featured in art like Persepolis. They signified dignity in Ancient Egypt, often appearing over gods.

- Parasol (Spanish or French) is a combination of para, to stop or to shield and sol, meaning sun. The French call umbrellas parapluie, shields from rain. (Parachute means “shield from fall.”) Umbrella comes from Latin, umbel, a flat-topped rounded flower and umbra, shaded or shadow.

- In Ancient Greece, parasols were items of female fashion. In Aristophanes’ Birds, Prometheus uses one as a comical disguise to hide from Zeus.

- The first lightweight folding umbrella in Europe was introduced in 1710 by Jean Marius in Paris. He received the exclusive right to produce folding umbrellas for five years. The item became an essential fashion item for Parisiennes after Princess Palatine bought one 1712.

- In 1959, a French scientist combined it with a cane and a button that opened the umbrella. Their use became widespread in Paris and their prestige apparently plummeted. In 1768 a Paris magazine reported:

The common usage for quite some time now is not to go out without an umbrella, and to have the inconvenience of carrying it under your arm for six months in order to use it perhaps six times. Those who do not want to be mistaken for vulgar people much prefer to take the risk of being soaked, rather than to be regarded as someone who goes on foot; an umbrella is a sure sign of someone who doesn’t have his own carriage.

Planned Parenthood’s Origins

Amidst today’s hearing on Planned Parenthood in Congress, I thought it might be useful to look into its origins. I immediately thought to take a look at Margaret Sanger’s Wikipedia page and found her legal fights telling of what the world looked like without Planned Parenthood:

Margaret Sanger, a nurse who was the first president of the organization, had a series of legal fights before Planned Parenthood was formed. In 1916, she was charged for distributing contraceptions in her clinic in Brownesville, Brooklyn. Sanger was sentenced to 30 days in a workhouse, protested by going on a hunger strike and became the first woman to be force fed in the United States.

Margaret Sanger, a nurse who was the first president of the organization, had a series of legal fights before Planned Parenthood was formed. In 1916, she was charged for distributing contraceptions in her clinic in Brownesville, Brooklyn. Sanger was sentenced to 30 days in a workhouse, protested by going on a hunger strike and became the first woman to be force fed in the United States.

In 1918, Sanger’s appeal of her conviction set the precedent that exempted physicians from laws that prohibited the distribution of information about contraception. Her American Birth Control League proclaimed these principles in 1921:

In 1918, Sanger’s appeal of her conviction set the precedent that exempted physicians from laws that prohibited the distribution of information about contraception. Her American Birth Control League proclaimed these principles in 1921:

We hold that children should be (1) Conceived in love; (2) Born of the mother’s conscious desire; (3) And only begotten under conditions which render possible the heritage of health. Therefore we hold that every woman must possess the power and freedom to prevent conception except when these conditions can be satisfied.

Over the next two decades, Sanger would write letters and give lectures in favor of birth control. She ordered a diaphragm from overseas in 1932, violating a law that forbid physicians from ordering contraceptions. She would win that appeal in 1936. Sanger’s efforts with a variety of lobbying organizations and contraception providers would culminate in Planned Parenthood’s formation in 1946.

Sanger’s beliefs are often described as radical by opponents of abortion but you could also use that term to describe a world where writing about or purchasing contraception is considered a crime.

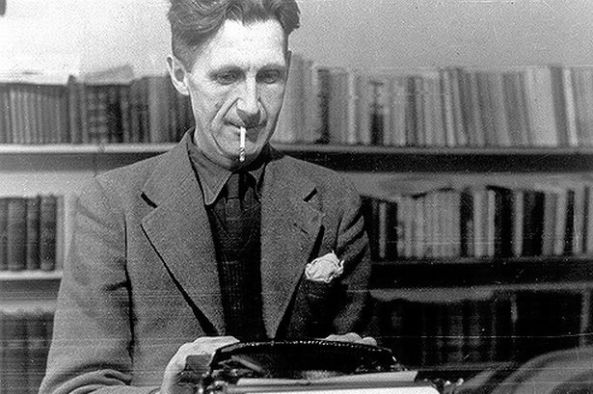

George Orwell on Political Writing

I’ve been meaning to assess Bernie Sanders and his brand of “democratic socialism” compared to George Orwell’s definition. But I haven’t found quite the right angle to hit now that we know that Sanders would continue the U.S. drone program in a limited fashion.

Nevertheless, these two paragraphs from Orwell’s “Why I Write” will have to suffice until I can strip democratic socialism down to its essential points:

Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one’s political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one’s aesthetic and intellectual integrity.

What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.

Though still a politician, Sanders would likely agree with Orwell’s self-description:

I am definitely “left,” but I believe that a writer can only remain honest if he keeps free of party labels.